- Home

- Anne Warner

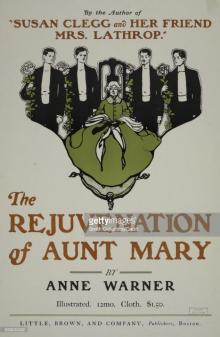

The Rejuvenation of Aunt Mary

The Rejuvenation of Aunt Mary Read online

The Rejuvenation of Aunt MaryBy Anne Warner

Author of "A Woman's Will," "Susan Clegg and Her Friend Mrs. Lathrop,""Susan Clegg and a Man in the House," etc._NEW EDITION__With Additional Pictures from the Play_

BostonLittle, Brown, and Company1910

_Copyright, 1904,_ By Ainslee Magazine Company.

_Copyright, 1905,_ By Little, Brown, and Company.

_Copyright, 1907,_ By Little, Brown, and Company,

_All rights reserved_

Fourteenth Printing

Printers S.J. Parkhill & Co., Boston, U.S.A.

[_Frontispiece_]

Aunt Mary en Fete. May Robson as "Aunt Mary."

_Books by Anne Warner_A Woman's Will 1904Susan Clegg and Her 1904Friend Mrs. LathropThe Rejuvenation of Aunt 1905MarySusan Clegg and Her 1906Neighbor's AffairsSusan Clegg and a Man in 1907the HouseAn Original Gentleman 1908In a Mysterious Way 1909Your Child and Mine 1909

CONTENTS

IllustrationsChapter One - Introducing Aunt MaryChapter Two - JackChapter Three - Introducing JackChapter Four - MarriedChapter Five - The Day After Falling in LoveChapter Six - The Other ManChapter Seven - DevelopmentsChapter Eight - The Resolution He TookChapter Nine - The Downfall of HopeChapter Ten - The Woes of the Disinherited.Chapter Eleven - The Dove of PeaceChapter Twelve - A Trap For Aunt MaryChapter Thirteen - Aunt Mary EntrappedChapter Fourteen - Aunt Mary En FeteChapter Fifteen - Aunt Mary EnthralledChapter Sixteen - A Reposeful IntervalChapter Seventeen - Aunt Mary's Night About TownChapter Eighteen - A Departure And A ReturnChapter Nineteen - Aunt Mary's ReturnChapter Twenty - Jack's JoyChapter Twenty-One - The Peace and Quiet of the CountryChapter Twenty-Two - "Granite"Chapter Twenty-Three - "Granite" - Continued.Chapter Twenty-Four - Two Are CompanyChapter Twenty-Five - Grand Finale

ILLUSTRATIONS

"Aunt Mary en fete" (May Robson as "Aunt Mary") _Frontispiece_ "'Do not let us play any longer,' she said. 'Let us be in earnest'" "'She's goin' to the city all alone!' Lucinda's voice suddenly proclaimed behind him" Aunt Mary and Her Escorts "The carriage stopped three hundred feet below the level of a roof-garden" "And now the fun's all over and the work begins" "'Yesterday I played poker until I didn't know a blue chip from a white one'" "Aunt Mary had also had her eyes open"

THE REJUVENATION OF AUNT MARY

CHAPTER ONE - INTRODUCING AUNT MARY

The first time that Jack was threatened with expulsion from college hisAunt Mary was much surprised and decidedly vexed--mainly at the college.His family were less surprised, viewing the young man through a cleareratmosphere than his Aunt Mary ever had, and knowing that he had barelyescaped similar experiences earlier in his career by invariably leavingschool the day before the board of inquiry convened.

Jack's preparatory days having been more or less tempestous, his family(Aunt Mary excepted) had expected some sort of after-clap when he enteredcollege. Nevertheless, they had fervently hoped that it would not be quiteas bad as this.

Jack's sister Arethusa was visiting her aunt when the news came. Notbecause she wanted to, for the old lady was dreadfully deaf and fearfullyarbitrary, but because Lucinda had said that she must go to her cousin'swedding, and the family always had to bow to Lucinda's mandates. Lucindawas Aunt Mary's maid, but she had become so indispensable as a sitter atthe off-end of the latter's ear-trumpet that none of the grand-nephews orgrand-nieces ever thought for an instant of crossing one of her wishes. Soit was to Arethusa that the explanations due Aunt Mary's interest in herscapegrace fell, and she bowed her back to the burden with the resignationwhich the circumstances demanded.

"Whatever is the difference between bein' expelled and bein' suspended?"Aunt Mary demanded, in her tone of imperious impatience. "Well, why don'tyou answer? I was brought up to speak when you're spoken to, an' I'm agreat believer in livin' up to your bringin' up--if you had a good one.What's the difference, an' which costs most? That's what I want to know. Ido wish you'd answer me, Arethusa; there's two things I've asked you now,an' you suckin' your finger an' puttin' on your thimble as if you weresittin' alone in China."

"I don't know which costs most," Arethusa shrieked.

"You needn't scream so," said Aunt Mary. "I ain't so hard to hear as youthink. I ain't but seventy, and I'll beg you to remember _that_, Arethusa.Besides, I don't want to hear you talk. I just want to hear about Jack.I'm askin' about his bein' expelled and suspended, an' what's thedifference, an' in particular if there's anything to pay for broken glass.It's always broken glass! That boy's bills for broken glass have beensomethin' just awful these last two years. Well, why don't you answer?"

"I don't know what to answer," Arethusa screamed.

"What do you suppose he's done, anyhow?"

"Something bad."

Aunt Mary frowned.

"I ain't mad," she said sharply. "What made you think I was mad? I ain'tmad at all! I'm just askin' what's the difference between bein' expelledan' bein' suspended, an' it seems to me this is the third time I've askedit. Seems to me it is."

Arethusa laid down her work, drew a mighty breath, very nearly got intothe ear-trumpet, and explained that being suspended was infinitely lessheinous than being expelled, and decidedly less final.

Aunt Mary looked relieved.

"Oh, then he's gettin' better, is he?" she said. "Well, I'm sure that'ssome comfort."

And then there was a long pause, during which she appeared to be engagedin deep reflection, and her niece continued her embroidery in peace. Thepause endured until a sudden sneeze on the part of the old lady set thewheels of conversation turning again.

"Arethusa," she said, "I wish you'd go an' get the ink an' write to Mr.Stebbins. I want him to begin to look up another college with goodreferences right away. I don't want to waste any of the boy's life, an' ifbein' suspended means waitin' while the college takes its time to considerwhether it wants him back again or not I ain't goin' to wait. I'm a greatbeliever in a college education, but I don't know that it cuts much figurewhether it's the same college right through or not. Anyway, you write Mr.Stebbins."

Arethusa obeyed, and the authorities having seen fit to be uncommonlydiscreet as to the cause of the young man's withdrawal, no greatdifficulty was experienced in finding another campus whereon Aunt Mary'spride and joy might freely disport himself. Mr. Stebbins threw himselfinto the affair with all the tact and ardor of an experienced legal mindand soon after Lucinda's return to her home allowed Arethusa to followsuit, the hopeful younger brother of the latter became a candidate for hissecond outfit of new sweaters and hat bands that year.

Aunt Mary wrote him a letter upon the occasion of his new start in life,Mr. Stebbins delivered him a lecture, and things went smoothly inconsequence for three whole weeks. I say three whole weeks because threewhole weeks was a long time for the course of Jack's life to flowsmoothly. At the end of a fortnight affairs were always due to run morerapidly and three weeks produced, as a general thing, some species ofclimax.

The climax in this case came to time as usual his evil genius inciting theyoung man to attempt, one very dark night, the shooting of a cat which hethought he saw upon the back fence. Whether he really had seen a cat ornot mattered very little in the later development of the matter. He wascertainly successful as far as the going off of the gun was concerned, butthe damage that resulted, resulted not to any cat, but to the arm of anext-door's cook, who

was peacefully engaged in taking in her week's washon the other side of the fence. The cook ceased abruptly to take in thewash, the affair was at once what is technically termed looked into, andthree days later Jack became the defendant in a suit for damages.

Naturally Mr. Stebbins was at once notified and he had no choice except towrite Aunt Mary.

Aunt Mary was somewhat less patient over the third escapade than she hadbeen with the first two.

The letter found her alone with Lucinda and she read it to herself threetimes and then read it aloud to her companion. Lucinda, whose thoroughknowledge of the imperious will and impervious eardrums of her mistressrendered her, as a rule, extremely monosyllabic, not to say silent,vouchsafed no comment upon the contents of the epistle, and after a fewminutes Aunt Mary herself took the field:

"Now, what do you suppose possessed that boy to shoot at a cook?" sheasked, regarding the letter with a portentous frown. "Cooks are so awfulhard to get nowadays. I don't see why he didn't shoot a tramp if he had toshoot somethin'."

"He wa'n't tryin' to shoot a cook, 'pears like," then criedLucinda--Lucinda's voice, be it said, _en passant_, was of that sibilantand penetrating timbre which is best illustrated in the accents of asteamfitter's file--"'pears like he was tryin' for a cat."

"Not a bat," said her mistress correctively; "it was a cat. You look atthis letter an' you'll see. And, anyway, how could a man shootin' at a cathit a cook?--not 'nless she was up a tree birds'-nestin' after owls' eggs.You don't seem to pay much attention to what I read to you, Lucinda; onlyI should think your commonsense would help you out some when it comes to aboy you've known from the time he could walk, an' a strange cook. But,anyhow, that's neither here nor there. The question that bothers me is,what's to pay with this damage suit? I think myself five hundred dollarsis too much for any cook's arm. A cook ain't in no such vital need of twoarms. If she has to shut the door of the oven while she's stirrin'somethin' on the top of the stove, she can easy kick it to with her foot.It won't be for long, anyway, and I'm a great believer in making the bestof things when you've got to."

Lucinda screwed up her face and made no comment. Lucinda's face in reposewas a cross between a monkey's and a peanut; screwed up, it wasparticularly awful, and always exasperated her mistress.

"Well, why don't you say somethin', Lucinda? I ain't askin' your advice,but, all the same, you can say anything if you've got a mind to."

"I ain't got a mind to say anythin'," the faithful maid rejoined.

"I guess you hit the nail on the head that time," said Aunt Mary, withoutany unnecessary malevolence concealed behind her sarcasm; then she re-readthe note and frowned afresh.

"Five hundred dollars is too much," she said again. "I'm going to write toMr. Stebbins an' tell him so to-night. He can compromise on two hundredand fifty, just as well as not. Get me some paper and my desk, Lucinda.Now get a spryness about you."

Lucinda laid aside her work and forthwith got a spryness about her,bringing her mistress' writing-desk with commendable alacrity. Aunt Marytook the writing-desk and wrote fiercely for some time, to the end thatshe finally wrote most of the fierceness out of herself.

"After all, boys will be boys," she said, as she sealed her letter, "andif this is the end I shan't feel it's money wasted. I'm a great believerin bein' patient. Most always, that is. Here, Lucinda you take this toJoshua and tell him to take it right to mail. Be prompt, now. I'm a greatbeliever in doin' things prompt."

Lucinda took the letter and was prompt. "She wants this letter took rightto the mail," she said to Joshua, Aunt Mary's longest-tried servitor.

"Then it'll be took right to mail," said Joshua.

"She's pretty mad," said Lucinda.

"Then she'll soon get over it," replied the other, taking up his hat andpreparing to depart for the barn forthwith.

Lucinda returned to Aunt Mary with a species of dried-up sigh. One is notthe less a slave because one has been enslaved for twenty years, andLucinda at moments did sort of peek out through her bars--possibly envyingJoshua the daily drives to mail when he had full control of something thatwas alive.

Lucinda had been, comparatively speaking, young when she had come to waitupon the pleasure of the Watkins millions, and her waiting had been sopertinent and so patient that it had endured over a quarter of a century.Aunt Mary had been under fifty in the hour of Lucinda's dawn; she was overseventy now. Jack hadn't been born then; he was in college now; and Jack'solder brothers and sisters and his dead-and-gone father and mother hadbeen living somewhere out West then, quite hopeful as to their own livesand quite hopeless as to the stern old great-aunt who never had paid anyattention to her niece since she had chosen to elope with the doctor'sreprobate son. Now the father and mother were dead and buried, thebrothers and sisters reinstated in their rights and had all grown up andbecome great credits to the old lady, whose heart had suddenly melted atthe arrival of five orphans all at once. And there was only Jack tocontinue to worry about.

Jack was not anything particularly remarkable; he was just one of thoselovable good-for-nothings that seem born to get better people into troubleall their lives long. He had been spoiled originally by being ten yearsyounger than the next youngest in the family; and then, when the childrenhad been shipped on to Aunt Mary's tender mercies, Jack had won her heartimmediately because she accidentally discovered that he had never beenbaptized, and so felt fully justified in re-naming him after her ownfather and having the name branded into him for keeps by her own religiousapparatus. It followed naturally that John Watkins, Jr., Denham, for soher father's daughter had insisted that her youngest nephew should becalled, was the favorite nephew of his aunt.

And it was lucky for him that he was the favorite, for Aunt Mary, who washighly spiced at fifty, became peppery at sixty, and almost biting atseventy. And yet for Jack she would sign checks almost without a murmur.Mr. Stebbins was much more censorious and impatient with the young manthan she ever was; and to all the rest of the world Mr. Stebbins was anurbane and agreeable gentleman, whereas to all the rest of the world AuntMary was a problem or a terror. But Mr. Stebbins needed to be a man oftact and management, for he was the real manager of that fortune of which"Mary, only surviving child of John Watkins, merchant and ship owner," wasthe legal possessor; and so tactful was Mr. Stebbins that he and hispowerful client had never yet clashed, and they had been in close businessrelations for almost as many years as Lucinda had been established on thehearthstone of the Watkins home. Perhaps one reason why Mr. Stebbinsendured so well was that he had a real talent for compromising, and thathe had skillfully transformed Aunt Mary's inherited taste for driving abargain into an acquired pleasure in what is really a polite form of thesame action.

So, when it came to the matter of Jack's difficulties, Mr. Stebbins couldalways find a half-way measure that saved the situation; and when hereceived the letter as to the cook and her claim he hied himself to thecity at once, and wrote back that the claim could be settled for threehundred dollars.

"And enough, I must say," Aunt Mary remarked to Lucinda upon receipt ofthe statement; "three hundred dollars for one cat--for, after all, Jackblames the whole on the cat, an' he didn't hit it, even then."

Lucinda did not answer.

"But if the boy settles down now I shan't mind payin' the three--Where areyou goin'?"

For Lucinda was walking out of the room.

"I'm goin' to the door," said she raspingly. "The bell's ringin'."

After a minute or two she came back.

"Telegram!" she announced, handing the yellow envelope over.

Aunt Mary put on her glasses, opened it, and read:

Cook has blood poison. Sues for a thousand. Probable amputation.

STEBBINS.

Aunt Mary dropped the paper with a gasp.

Lucinda looked at her with interest.

"It's that same arm again," said Aunt Mary, "just as I thought it wassettled for!" Her eyes seemed to f

airly crackle with indignation. "Whydon't she put it in a sling an' have a little patience?"

Lucinda took the telegram and read it.

"'Pears like she can't," she commented, in a tone like a buzz saw; "'pearslike it's goin' to be took off."

Aunt Mary reached forth her hand for the telegram and after a secondreading shook her head in a way that, if her companion had been aglobe-trotter, would have brought matadores and Seville to the front inher mind in that instant.

"I declare," she said, "seems like I had enough on my mind without a cook,too. What's to be done now? I only know one thing! I ain't goin' to pay nothousand dollars this week for no arm that wasn't worth but three hundredlast week. Stands to reason that there ain't no reason in that. I guessyou'd better bring me my desk, Lucinda; I'm goin' to write to Mr.Stebbins, an' I'm goin' to write to Jack, and I'm goin' to tell 'em bothjust what I think. I'm goin' to write Jack that he'd better be lookin'out, and I'm goin' to write to Mr. Stebbins that next time he settlesthings I want him to take a receipt for that arm in full."

The letters were duly written and Mr. Stebbins, upon the receipt of his,redoubled his efforts, and did succeed in permanently settling with thecook, the arm being eventually saved. Aunt Mary regarded the sum as muchhigher than necessary, but still pleasantly less than that demanded ofher, and so life in general moved quietly on until Easter.

But Easter is always a period of more or less commotion in the time ofyouth and leads to various hilarious outbreaks. Jack's Easter took him totown for a "little time," and the "little time" ended in the station-houseat three o'clock on Sunday morning.

Accusation: Producing concussion of the brain on a cab driver.

Susan Clegg and Her Love Affairs

Susan Clegg and Her Love Affairs Susan Clegg and a Man in the House

Susan Clegg and a Man in the House Susan Clegg and Her Friend Mrs. Lathrop

Susan Clegg and Her Friend Mrs. Lathrop The Rejuvenation of Aunt Mary

The Rejuvenation of Aunt Mary Susan Clegg and Her Neighbors' Affairs

Susan Clegg and Her Neighbors' Affairs